Biografia

©1995 Mary Kent. All Rights Reserved.

Traduzione a cura di Silly

Eddie Torres è nato il 3 luglio 1950, nello stesso ospedale di Tito Puente ed è stato allevato dai genitori portoricani nello Spanish Harlem, conosciuto anche come El Barrio, nella città di New York. La mamma di Eddie, impiegata d’ospedale e suo padre, un estroso idraulico, stimolarono le capacità di Eddie verso la creatività. Per quanto ne sa Eddie, nella sua famiglia non c’era mai stata predisposizione genetica per il ballo o la musica.

Eddie aveva appena 12 anni quando gli venne il pallino del ballo. Appena tornato a New York dopo un soggiorno di due anni a Portorico, Eddie si prese una sonora cotta per una ragazza. Timidamente, lui le chiese di andare insieme al cinema e lei gli fece una controproposta: gli chiese di andare a casa sua. Quel sabato, quando Renée aprì la porta di casa, Eddie rimase sorpreso nel vedere un grande e bel ragazzo seduto sul divano. Renée, in tono di scusa, bisbigliò: “Lui è il mio ex ragazzo. Lui sta cercando di riconquistarmi”.

E poi, con l’intenzione di rompere la tensione, chiese a Eddie: “Tu conosci il Latino ?”; Renée voleva sapere se lui ballasse le danze latine. Ed Eddie, fresco del viaggio fatto a Portorico, era sicuro di poterlo fare. Renée si sporse verso il giradischi e fece cadere la puntina su un pezzo di Eddie Palmieri, “Azucar Pa’ Ti”. Pur non conoscendo nulla circa il portamento o il tempo, il giovane corteggiatore incominciò a saltare a destra e a sinistra e poi diede un occhio in giro per raccogliere sguardi di approvazione. Ma il suo rivale, accomodato sul divano, chiuse le mascelle saldamente, sforzandosi di non scoppiare in grandi risate.

In due minuti contati, Renée liquidò il suo partner inesperto, prese il suo ex ragazzo e spiegò in maniera professionale: “Lascia che io ti mostri come NOI balliamo il latino”. Fu semplice notare come ci fossero tanta coordinazione, ricchezza di figure e ogni sorta di giri. E più loro ballavano e più Eddie si sentiva male. Dopo la dimostrazione di ballo, Renée lo prese da parte e gli spiegò: “Lui vuole davvero riconquistarmi”. Da quel momento Eddie fece una promessa a se stesso: “Non dovrà più accadermi una cosa del genere. Imparerò a ballare”.

L’idea di imparare i balli latini divenne una vera ossessione. La sua istruzione prese la forma di andare in tutti i club e di frequentare tutti i ballerini più bravi, osservando, imitando, chiedendo, diventando un vero seccatore. Lentamente incominciò ad apprendere le basi del ballo. A quei tempi, non erano molti i locali che permettevano ai ragazzi di entrare, ma il famoso Hunts Point Palace apriva ogni domenica da mezzogiorno a mezzanotte e, per soli 5 dollari, proponeva 5 top band latine, in sequenza, su due palchi. Il quindicenne Eddie spaccava il secondo all’apertura e se ne usciva all’ora di chiusura, sfinito ma determinato a imparare.

Otto anni più tardi, Eddie insegnava e faceva gare di ballo e si era fatto la reputazione di essere uno dei migliori. Una notte, mentre stava ballando in una tenuta bianca da capo a piedi, in un club acceso da niente altro che luci ultraviolette, sua sorella lo stese. Sembra che Renée, la sua fiamma di gioventù, si fosse accorta di un ballerino capace e che volesse essergli presentata. Nel buio, la sorella di Eddie fece le presentazioni: “Renée, voglio presentarti Eddie”. Avendo riconosciuto il bravo ballerino, Renée rimase di ghiaccio, sbigottita come se avesse visto dieci fantasmi. Eddie voleva ballare con lei a tutti i costi, la voleva ringraziare: “Tu sei la ragione che mi ha portato fino a questo punto”. Ma lei si dileguò e questa fu l’ultima volta che Eddie la vide.

IMPARARE LE BASI

Non c’erano locali dove si potesse imparare a ballare questo stile, quindi l’ambiente dei nightclub era quello che alimentava la nascita di aspiranti ballerini. E non tutti i ballerini erano generosi. “C’erano ballerini che non avrebbero mai voluto che tu osservassi i loro passi, perchè non volevano che tu imparassi: Questo è un affare privato !” Fortunatamente per Eddie, egli ebbe la capacità di far suoi dei passi solo guardando. Lui ebbe modo di guardare ballerini come Louie Maquina, che aveva questo soprannome per il suo gioco di piedi “veloce ed infuocato”; Gerard, un ballerino conosciuto per le sue scandalose performances; George Boscones, l’insegnante di molti principianti e soprattutto Jo-Jo Smith, un insegnante jazz professionista con uno stile unico nel ballare il mambo jazz.

I professionisti di quel periodo erano Freddy Rios, l’asso del Cha Cha, Tommy Johnson e un team che influenzò tutti quanti, il team leader del momento: Augie e Margo. Dopo la prima volta che Eddie li vide a Roseland, rimase in uno stato tale di euforia che non potè dormire per intere settimane. Eddie continuava a pensare: “Voglio essere Augie e devo trovare la mia Margo”.

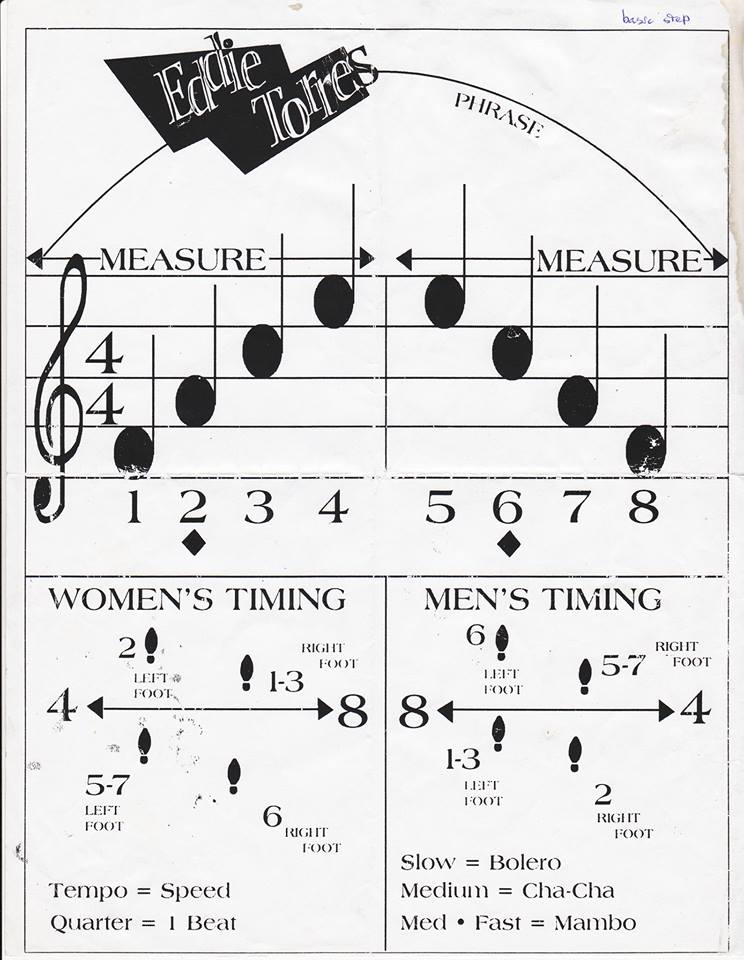

Non appena ebbe imparato a fare le cose che facevano gli altri, aprì una scuola dove lui potesse insegnare, perchè voleva condivedere la sua conoscenza. Con un fonografo preso in affitto e con un gruppo di amici, entrò presto nel business. Fuori dal concetto di tempo, tecnica e teoria, la sua istruzione consisteva in questi punti rudimentali: “Tu senti l’accento ? Questo significa che tu devi andare avanti con il sinistro e quando lo senti ancora, devi portarlo indietro”. Questa tecnica è conosciuta come “ballare sul due”, ed è quello che Eddie presto scoprì. Il Break on two significava che dei quattro tempi musicali, tu devi portare avanti il piede sinistro sulla seconda battuta e sulla seconda battuta della seconda parte tu devi portare indietro il piede destro. Secondo il mentore di Eddie, Tito Puente, questo è il motivo per cui il break on two è così popolare, perchè esso asseconda il tumbao delle conga e tutta la sezione ritmica.

TITO, PLEASE

Dall’ottobre del 1975 fino al 1986 circa, il nightclub Corso sulla 86esima strada divenne la dimora della seconda generazione dell’era del Palladium. Mercoledì, venerdì, sabato e domenica vi si poteva trovare Eddie Torres che si dilettava nei suoi passi per la gioia di Tito Puente e di Machito. Fin dall’inizio, la musica di Tito Puente gli parlò. Questo durò per tutti gli anni che Puente ebbe quel gruppo di scapestrati assieme a Santos Colon. Testando la sua abilità nelle gare di ballo, Torres si aggiudicò così tanti premi che a un certo punto Marty Ahret, il titolare del Corso, gli chiese di uscire dalle competizoni e di fare il giudice.

Una domenica sera, mentre Tito Puente lasciava il palco, Eddie si avvicinò al maestro per fargli i complimenti. Tito, che aveva percepito il talento di Eddie, gli disse: “Tu hai talento per il ballo. Ma hai bisogno di fare qualcosa di più che passare tutto il tuo tempo qui nei balli sociali”. “Non ci sono insegnanti”, ribattè Eddie. Tito fece un balzo e gli disse: “Dimenticati dei mentori. Sviluppa da solo le tue idee e mettile insieme. Capisci come da solo”. Sbigottito, Eddie insistette: “Ammesso che io abbia un’idea, potremmo fare del lavoro insieme ?” “Metti insieme qualcosa e mostramelo”. Tutto quello che Eddie aveva sempre voluto era di ballare per il gruppo di Tito.

Otto anni prima Eddie incontrò Maria, sua futura moglie e partner di ballo. Gli anni passati a ballare e a osservare lo avevano portato ad acquisire una tecnica e uno stile unici. Maria, che insegnava educazione fisica ai bambini, inizialmente si sentiva piuttosto intimidita, ma velocemente diventò la migliore studente di Eddie, imparando più velocemente di chiunque a cui lui avesse mai insegnato. “Se io facevo un passo, lei lo ripeteva giusto dietro di me”. Ma il suo stile era provinciale e mancava dell’influenza di New York. Spinto dall’idea di riuscire, Eddie coreografò i suoi primi due motivi, El Cayuco e Palladium Days di Tito Puente, e li insegnò a Maria. In meno di un anno, Maria divenne una brava ballerina ma non aveva ancora abbastanza esperienza per esibirsi nei club. Così, quando Eddie presentò Maria ai club come sua nuova partner, i suoi amici non pensavano che lei ce l’avrebbe fatta. Un paio d’anni più tardi, gli stessi ammisero: “Lo sai, Eddie, sta crescendo bene”. Dopo tre anni, erano tutti d’accordo nel dire che lei era la migliore partner che lui avesse mai avuto.

Pieno di entusiasmo per il lavoro della sua partner, Eddie decise che era ora di parlarne a Tito. In occasione di un’esibizione al Christopher Cafè, nel Barrio, Mr Puente riconobbe Eddie e gli disse: “Tu sei il ballerino del Corso”. Torres gli offrì un improvvisato biglietto da visita e rilanciò: “Pensi che io possa venire insieme alla mia partner a farti vedere questi due numeri che ho coreografato ? Se ti piacciono, potremmo fare uno spettacolo con te ?” Tito non misurò le parole: “Lo sai, sarò sincero con te, Eddie. Sono molto occupato in questo momento. Non penso che avrò l’occasione di chiamarti…”. Eddie ci rimase male. “…Ma ti dirò io cosa farò. Io ho intenzione di presentarti il mio musical director, Jimmy Frisaura. Dì esattamente a Jimmy cosa vuoi trovare nella musica, come vuoi che noi la suoniamo e nel nostro prossimo concerto, io presenterò te e la tua partner”. Eddie rimase sbalordito.

L’anno era il 1980. Fu un sogno che diveniva realtà, il debutto con Tito Puente prese vita nel Colosseo di New York, come parte di una grande fiera latina. Eddie era davvero nervoso, ma lui e la sua partner, Maria, erano molto preparati. Si esibirono prima su Cayuco e poi su Palladium Days. La gente ne rimase affascinata e sul volto di Tito comparve un bellissimo sorriso. Fu un successo pazzesco.

Eddie Torres & Tito Puente impegnati in un’amichevole discussione.

Da quel giorno in poi, ovunque Tito andasse, Eddie lo seguiva con i costumi di scena e le scarpe, sempre pronto. E Tito spesso chiedeva: “Ragazzi, avete voglia di fare questa esibizione ?” Erano esibizioni non retribuite, ma Torres si sentiva privilegiato a lavorare con Tito. Alla fine, Torres divenne parte integrante dello show. In seguito domandò: “Tito, ti dispiacerebbe se noi ci chiamassimo i “Tito Puente dancers” ?”. Quel sogno, di venire identificato come il corpo di ballo di Tito, divenne realtà con un giubbino con la foto di Tito Puente che suonava i timbales, e la scritta “Tito Puente Dancers”. Fu un grandissimo onore per Eddie. E lo fu anche maggiore quando Jimmy Frisaura ammise: “Tito non condivide il palco con chiunque troppo facilmente. Tu gli piaci”.

NOI VOGLIAMO IL LATINO

Alla metà degli anni ottanta, il latino non era di moda mentre la disco sì ed era davvero difficile ottenere un lavoro come ballerino. In un’occasione, Eddie volle ballare durante un concerto latino al Madison Square Garden dove Tito Puente si stava esibendo, ma Ralph Mercado disse: “No, no, no. Io ho i Disco Dance Dimensions per gli intermezzi. Non c’è motivo per cui tu ti esibisca. Questo non è quello che la gente vuole”. Ferito e demoralizzato, Eddie spiegò la sua frustrazione a Tito: “Io non voglio soldi. Io voglio solo uscire sul palco e fare quel che so fare con te”. Tito lo rassicurò: “Non ti preoccupare, caro. Io ti porterò con me come la “Tito Puente Dancers” e dirò a Ralphy che non si deve preoccupare di nulla”.

Ralph Mercado, RMM

La notte del concerto, i Disco Dance Dimensions misero in piedi uno show che doveva piacere alla massa. Subito dopo, Tito Puente suonò “Para Los Rumberos” e fece impazzire il pubblico. Dopodichè, invitò sul palco il duo di ballerini ad esibirsi su Palladium Days, un mambo molto intenso e focoso. In maniera decisa, Eddie ricordò a Maria: “Voglio che tu balli sanguigna”. Ballarono davvero come se fossero sul fuoco. Tito fece un gran bel sorriso. E un compiaciuto Ralph Mercado osservò lo spettacolo dalle quinte. Il pubblico rumoroso rese loro una standing ovation, e questo costituì un chiaro messaggio: la gente preferiva assistere a delle esibizioni di balli latini che accompagnavano la musica latina. Volevano che Ralph e tutti sapessero: ”Hey, questo è quello che vogliamo”.

Dopo quella sera, Ralph Mercado incominciò a chiamare Eddie a esibirsi con lui. Negli anni novanta, Ralph lanciò il suo affascinante gruppo di ballo, chiamato “The RMM Dancers”, che animava i suoi concerti con eleganti esibizioni di salsa, sebbene il gruppo di Eddie continuasse ad apparire nelle serate del RMM.

IL FUTURO

Nel corso degli anni ottanta, quando Maria e Eddie salirono sulle scene, erano rimasti solo poche scuole di ballo dirette da professionisti. A parte Ernie e Dottie e gli Assi del Cha Cha, era rimasta solo una piccola traccia della grande era del Palladium. Pare che i ballerini del Palladium si divertissero così tanto a ballare per se stessi che non pensavano alle generazioni che sarebbero seguite.

Presto, Eddie sviluppò una nuova idea, quella di vedere i balli latini evolversi verso una forma rispettata e classica di arte. Riconoscendo la necessità di tramandare le tradizioni della musica e del ballo alle generazioni a venire, Mr Torres si prese questa missione per fare in modo che accadesse. La gente gli rideva in faccia: “Eddie, cosa stai facendo ? Questo ballo è morto”. Ma lui, con ostinazione, continuava nella sua missione.

Prima dell’arrivo di Eddie Torres, nessuno aveva formalizzato i concetti della struttura e della tecnica. Lui ha insegnato a migliaia di adepti dei balli latini. Il suo programma di ballo per bambini nel Bronx insegna, più o meno, a trecento bambini all’anno, inclusa la figlia di dieci anni di Eddie, Nadia, che è già una navigata professionista. L’idea singolare di offrire salsa e mambo ai bambini, assieme ad altre forme di danza, come il balletto classico, il jazz, il tip tap, il moderno o l’afro, garantisce il futuro del ballo latino. Il programma sviluppato da Eddie viene ora portato avanti da Maria.

LUI HA STILE

Quando il ballo latino arrivò a New York, era una danza di impostazione aperta. Ciò significa che i due ballerini danzavano uno di fronte all’altro e non c’era molto contatto, cioè quello che noi adesso conosciamo come ballo di coppia. Ma la seconda generazione dopo il Palladium si buttò nel fare tanto ballo di coppia. Sembra esserci un fascino particolare nell’inventare giri e nell’essere in contatto con il partner. I ballerini del Palladium hanno brevettato il New York style nell’ambito del ballo latino. “A New York alla gente gente piace vestire e parlare sciolto, essere jazz style. Specialmente i latini. Essere nati e cresciuti in Harlem, ti dà una certa impronta nel modo di camminare per la strada, nel modo di dire le cose e nel modo di usare il linguaggio del corpo. Ti dà un tale stile che, se io vedessi qualcuno di New York ballare in Giappone, lo riconoscerei.”

I musical di Broadway, il lavoro di Ailey, la danza afro e il flamenco furono tutte sorgenti di ispirazione per Eddie. Osservando, imitando ed ammirando i migliori di ogni stile, Eddie lentamente si evolse come professionista. Il suo stile è un’amalgama di tutti quelli che erano venuti prima di lui. Con un’innata capacità di imitare, ha incorporato un pò di jazz, un pò di balletto classico, un pò di tip tap, un pò di danza moderna, e se ne è venuto fuori con il suo stile personale. Osservando i diversi ballerini del suo tempo, con le loro impronte personali, ha preso da ciascuno del loro stili: i movimenti jazz e lo stile di espressione di Jo Jo Smith; lo stile tipicamente cubano di Freddy Rios; e un pò di Louie Maquina. Nel ballo questo è detto “stile eclettico”.

IL REPERTORIO DI TORRES

L’anziana June Laberta, un’insegnante di ballo da sala, influenzò maggiormente Eddie. Insegnava ogni tipo di ballo da sala, ma il suo più grande amore era il mambo. In molte occasioni, June accompagnò Eddie al Corso, dove la strana coppia infuriava. Lui aveva vent’anni, lei era alla fine dei cinquanta. Creando intricati e piccoli movimenti che venivano dal jazz e da tutto quello che conosceva, l’esile Laberta girava come una trottola.

La scuola di June fu determinante per la carriera di maestro di Eddie. Lei gli diceva: “Eddie io ti posso aiutare a imparare il linguaggio dell’insegnamento”. Lei lo portava nelle sale da ballo i venerdì sera, mettendolo in guardia. “Queste persone sono allievi e appassionati della danza. Se tu non fai il break on two, se non sei coerente con il tuo tempo, o se ti fanno domande sulla teoria e tu non sai rispondere, lo useranno contro di te”. Chiaramente, dopo aver fatto il suo strabiliante lavoro con i piedi, si sentì fare la temuta domanda: “Fai il break on two ?”. A quel tempo questi punti teorici sulla clave e sul ballo non scuotevano Eddie. Fortunatamente per Eddie, aveva ballato sul due per tutta la vita, solo che non lo sapeva. E June continuava a insistere: “Ti arricchirà come ballerino, come insegnante e come coreografo. Farai tanta strada con questa conoscenza”. Ma Eddie non se ne curava. Passarono quindici anni prima che se ne rese davvero conto.

Grazie a June Laberta, tutti i passi di Eddie hanno il loro nome. Questo repertorio di passi e giri, con i loro nomi corrispondenti, consente di interfacciarsi con gli studenti in modo accademico. Il programma di studio di Eddie, che documenta trecento passi, stranamente ricalca le abitudini dei vecchi studenti di danza nelle sale da ballo. Qualche volta nasce un passo solo con un piccolo break o una piccola sequenza. Oggi, gran parte del divertimento sta nell’inventare un passo e poi trovargli un nome.

Oggi, gli allievi stanno superando le persone che hanno ballato per tanti anni. Torres riceve parecchie chiamate di questo tipo: “Sono un grande ballerino, la gente si ferma a guardarmi”. Poi visitano la classe e rimangono di stucco. Il talento naturale è un plus ma Torres ammonisce: “Noi latini crediamo di poter camminare sulla pista e che lo possiamo fare perchè siamo latini e ce l’abbiamo nel sangue. Niente di più sbagliato”.

“Ho ballato oltre la gioia, oltre il dolore.

Questo è il tipo di ballo per cui se tu vuoi saltar su in piedi e dire “Azucar !” come Celia, e se tu vuoi muovere le spalle e scuotere la tua testa, lo puoi fare ed è ok. É fantastico. Ed è alla moda. Tu puoi essere te stesso.”

Noi dobbiamo ringraziare Tito Puente che ha mostrato, nella maggior parte dei suoi concerti, spettacoli di salsa e per aver fatto discorsi circa l’importanza del ballo ogni volta che ha presentato i nostri amati ballerini latini.

I risultati di Eddie includono sue molte collaborazioni con la Tito Puente Orchestra, coreografando video musicali per artisti come Ruben Blades, Orquesta de la Luz, Tito Nieves, José Alberto El Canario, David Byrne, scoprendo una compagnia di ballo, danzando per il Presidente George Bush, esibendosi al Carnegie Hall, all’Apollo Theater, al Madison Square Garden.

Tratto da: www.eddietorres.com

Biography

Salsa Dancing New York Style

©1995 Mary Kent. All Rights Reserved.

He was born July 3,1950 in the same hospital as Tito Puente; raised by his Puerto Rican parents in Spanish Harlem, a.k.a. El Barrio, New York City. Torres’s mother, a hospital worker; his father an inventive plumber, sparked Eddie’s knack for inventing. No dancers or musicians in the gene pool to Eddie’s best knowledge.

He was merely 12 years old when he caught the dancing bug. Just back in New York after a two year sojourn in Puerto Rico, he developed a puppy-love crush on a girl from the hood. Shyly, he asked her to the movies and she made a counter-offer: why didn’t he come to her house? That Saturday, when Renée opened the door, Eddie was surprised to see a tall, good-looking guy sitting on the couch. Renée whispered apologetically, “He’s my ex-boyfriend. He’s looking to make up with me.” Then, in an attempt to break the tension, she asked Eddie, “Do you know how to Latin?” She wanted to know if he knew how to dance Latin. Fresh from Puerto Rico, his confidence emboldened him. Renée leaned over the record player and dropped the needle on the groove of Eddie Palmieri’s Azucar Pa’ Ti. Not knowing a thing about leading position or about timing, the young suitor started jumping around, then glanced over to collect looks of approval. But his rival on the couch sat clamping his jaw closed, holding back a burst of laughter. Two minutes into the number, Renée retired her inexperienced partner, pulled her ex-boyfriend up and explained in a professorial manner, “Let me show you the way WE do the Latin.” It was plain to see that there was a lot of coordination, plenty of moving together and all sorts of turns. The more they danced, the worse Eddie felt. After the dance demonstration, his love interest pulled him to one side and explained, “He really wants to make up with me.” From that moment, Eddie made himself a promise, “This is never going to happen to me again. I’m going to learn how to dance.”

The idea of learning “to dance Latin” became an obsession. Schooling took the form of going to all the clubs and hanging out with all the good dancers–watching, imitating, asking, and being a pest. Slowly he started to learn the foundations of the dance.

In those days, not many clubs allowed teenagers in, but the famous Hunts Point Palace opened every Sunday from noon to midnight, and for $5, they presented five top Latin bands, back-to-back, on two stages.

Fifteen-year-old Eddie punched the clock when the club opened and sauntered out at closing time, exhausted but determined to learn.

Eight years later, he was teaching and competing in dance contests and garnering a reputation amongst the good dancers as being one of the best. One night, while he was dancing in a head-to-toe white outfit, in a club lit with nothing but black lights, his sister pulled him off the floor. It seems Renée, his childhood flame, spotted a slick dancer and wanted an intro. In the dark, Eddie’s sister did the honors.”Renée, I want you to meet Eddie.” Upon recognizing the skillful dancer, she froze as if she’d seen ten ghosts. Eddie wanted to dance with her desperately, he wanted to thank her, “You’re the reason why I got into this.” But she disappeared and that was the last time he saw her.

LEARNING THE BASICS There were no studios where one could learn how to dance this style, so the nightclub scene was the nurturing ground for aspiring dancers. And not all dancers were generous. “There were dancers who didn’t even want you to look at their steps, ‘cause they didn’t want you to learn: That’s private stock!” Lucky for Eddie, he had a knack for picking up steps just by watching. He observed dancers like Louie Máquina, who got his nickname from his “real rapid-fire footwork”; Gerard, a dancer known for his scandalous antics on the floor; George Boscones, the teacher of the newcomers and especially Jo-Jo Smith, a professional jazz teacher with a unique style of mambo jazz dancing.

The pros of that time were Freddy Rios, the Cha Cha Aces, Tommy Johnson and the one team who were the greatest influence of all, the prima donna team: Augie and Margo. After the first time Eddie saw them at Roseland, he was in such a state of euphoria that he couldn’t sleep for weeks. He kept thinking, “I want to be Augie and I have to find Margo.”

As soon as he learned to hold his own, he set up shop as a dance teacher, because he wanted to share his knowledge. Armed with a rented phonograph and a bunch of friends, he was soon in business. With no concept of timing, technique or theory, his instruction consisted of rudimentary pointers: “You hear that accent? That means you break forward with the left foot and when you hear it again, you break back.” This is known as dancing on two, Eddie would soon find out.

Breaking on two meant that of a four beat measure, you stepped forward with the left foot on the second beat and on the second beat second measure you stepped back on the right foot. According to Eddie’s mentor, Tito Puente, that’s why beat two is so popular, because it compliments the tumbao of the conga and the rhythm section.

TITO, PLEASE

From 1975 to about 1986, the Corso nightclub on East 86th Street became home to the second generation of the Palladium era. Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays found Eddie Torres strutting his Harlem steps to the likes of T.P. and Machito. From the beginning, Tito Puente’s music really spoke to him. This was during the years that Puente had the ass-kicking band with Santos Colón. Testing his skill in dance contests, Torres garnered so many awards that at one point, Marty Ahret, Corso’s owner, asked him to sit out the contests and judge.

One Sunday evening, as Tito Puente came off the stage, Eddie approached the maestro to pay his compliments. Tito perceived Eddie’s flair, “You’ve got talent for dancing. You need to do something more than just spend all your time here dancing socially.”

“There’s no mentors,” Eddie retorted. Tito whipped around, “Forget about mentors. Develop your own ideas and put a little act together. Figure it out yourself.” Emboldened, Eddie persisted, “If I had an act, could we do some work together?” “Get something together and show me.” All Eddie ever wanted to do was to dance with Tito’s band.

Eight years lapsed before Eddie met Maria, his future wife and partner. His years of dancing and observing had evolved into a unique technique and style. Maria, a children’s gymnastics teacher, felt rather intimidated at first, but quickly became Eddie’s best student, learning faster than anyone he’d ever taught.

“I would do a step and she would reflect it right back to me.” But her style was provincial and lacked the Big Apple pizazz. Prompted by the possibilities, Eddie choreographed his first two tunes, El Cayuco and Palladium Days by Tito Puente, and trained Maria. In less than a year, she became a good stage dancer, but she didn’t have any experience in club dancing. So when Eddie introduced Maria at the clubs as his new partner, his friends didn’t think she had it. A couple of years later, they conceded, “You know, Eddie, she’s getting pretty good.” By the third year, they agreed, she was the best partner he’d ever had.

Filled with enthusiasm over his partner work, Eddie decided it was time to talk to Tito. Performing at Christopher’s Cafe, in El Barrio, Mr. Puente spotted Eddie, “You’re the dancer from the Corso.” Torres offered him a makeshift business card, and pitched, “Do you think I can come over with my partner and demonstrate for you these two numbers that I choreographed? If you like them, maybe we could do a show with you?” Tito did not mince words, “You know, I’ll be honest with you, Eddie. I’m very busy right now. I don’t think I’ll have a chance to call you….”

Eddie frowned. “…But I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’m going to introduce you to my musical director, Jimmy Frisaura. Tell Jimmy exactly what you want in the music, how you want us to play it, and in our next concert, I’ll feature you with your partner.” Eddie was flabbergasted.

The year was 1980. It was a dream come true-the debut show with Tito Puente took place at the New York Coliseum as part of a big Latin Expo. Eddie was really nervous, but he and his partner, Maria, were very prepared. They performed Cayuco first and then broke out into Palladium Days. The crowd was captivated and Tito had a big smile on his face. It was a total success.

Eddie Torres & Tito Puente have a friendly discussion.

From that day forward, everywhere Tito went, Eddie would follow, costume and shoes, ready to go. And Tito would always ask, “You guys like to do a number?” It was ad honorem, but Torres felt privileged to be working with Tito. Eventually, Torres became a fixture–part of the format of the show. Then he popped the question, “Tito, would you mind if we call ourselves the Tito Puente Dancers?” That dream, to be identified as Tito’s dance team, took the form of a jacket with TP’s picture playing timbales–it said Tito Puente Dancers, and Tito dug it. It was Eddie’s biggest honor. Even more so when Jimmy Frisaura confided, “Tito doesn’t share the stage with anybody too readily. He likes you.”

WE WANT LATIN

In the mid-eighties, Latin was out and the hustle was in and it was very hard to get work as a Latin dancer. On one occasion, Eddie wanted to dance in a Latin concert at Madison Square Garden where Tito Puente was playing, but Ralph Mercado said, “Naw, no, no. I got the Disco Dance Dimensions for the intermission show.

I don’t see no need for you to be out there. That’s not what the people want.” Feeling hurt and upset, Eddie explained his frustration to Tito, “I’m not asking for money. I just want to go out and do my thing with you.” Tito assured him, “Don’t worry about it, baby. I’m gonna bring you in as the Tito Puente Dancers and I’m going to tell Ralphy he doesn’t have to worry about nothing.”

Ralph Mercado, RMM

The night of the concert, the Disco Dance Dimensions put on a crowd-pleasing show. Immediately after, Tito Puente played Para Los Rumberos, and got the crowd into a frenzy. Then, he signaled the dancing duo onto the stage to perform Palladium Days, a very fiery, intense mambo. Sternly, Eddie forewarned Maria, “I want you to dance blood.” They danced as if they were on fire. Tito had a big ol’ smile. And a pleased Ralph Mercado looked on from the sidelines. The roaring crowd in the Garden gave them a standing ovation, sending out a clear message: they preferred to see Latin dancing accompanying the Latin music. They wanted to let Ralph and everyone know, “Hey, that’s what we want.”

After that evening, Ralph Mercado started calling Eddie to do shows with him. In the nineties, Ralphy introduced his own captivating dance troupe called the RMM Dancers, who animate his concerts with sensuous salsa dancing, though Eddie’s group continues to appear at RMM gigs.

THE FUTURE

During the eighties, when Maria and Eddie came on the scene, only a few pro dance teams were left. Aside from Ernie and Dottie and the Cha Cha Aces, there was little trace of the powerful Palladium era. It seems the Palladium dancers got so caught up dancing for their own enjoyment that they weren’t thinking about future generations.

Early on, Eddie developed a vision: to see Latin dancing evolve to the point of a respected, classic art form. Recognizing the need to pass the traditions of the music and the dance on to future generations, Mr. T. took it upon himself to make it happen. People laughed at him, “Eddie, what are you doing? This dance is dead.” But he obstinately continued his mission.

Before Eddie Torres came along, no one had laid down concepts of structure and technique. He has taught thousands of Latin dance aficionados. His children’s dance program in the Bronx teaches approximately three hundred children throughout the year including Eddie’s ten year old daughter Nadia, who is already a seasoned pro. The unique idea of offering salsa or mambo dancing to children alongside other dance forms such as ballet, jazz, tap, modern or African, guarantees the future of Latin. The program developed by Eddie is now run by Maria.

HE’S GOT STYLE

When Latin dance first came to NY, it was an open position dance. That means that two dancers would dance in front of each other and there was not much contact, what we know today as partner work. But the second generation after the Palladium got into doing a lot of partner work. There seems to be a fascination for inventing turns and being in touch with the partner.

The Palladium dancers lay down the blue prints of the New York hip style of Latin dancing. “In NY, people like to dress slick, talk slick, to be very bebop jazzy. Especially Latinos. Being born and raised in Harlem carries a certain attitude about how you walk through the streets, attitude about the way you say things and how you use your body language. It carries such a signature that if I saw someone from New York dancing in Japan, I’d know it.”

Broadway musicals, Ailey’s work, African dancing, and flamenco all were sources of inspiration for Eddie.

Watching, imitating, and admiring the people that were the tops, Eddie slowly evolved as a pro. His style results from a true amalgamation of all those that came before him. With an uncanny ability to imitate, he incorporated a little jazz, a little ballet, a little tap, a little modern, and came out with his own style. Observing the different dancers of his time with their own signatures, he picked up from every one of their styles: JoJo Smith’s jazz movements and expression of style; Freddy Rios’s very Cuban typical style; a little of Louie Máquina. In dancing, that is known as eclectic styling.

THE TORRES REPERTOIRE

The late June Laberta, a ballroom dance teacher, was Eddie’s greatest influence. She taught every ballroom dance in the book, but her greatest love was mambo. On many occasions, June accompanied Eddie to the Corso where the odd couple danced up a storm. He was in his twenties, she was in her late fifties. Creating kooky intricate little moves that came from jazz and everything that she knew, the lean Laberta would spin like a top.

June’s mentoring was decisive in Eddie’s teaching career. She said, “Eddie, I can help you learn the language of teaching.” She took him to ballrooms on Friday nights warning, “These people are scholars and aficionados of the dance. If you don’t break on the two, if you’re not consistent with your timing, or if they ask questions about the theory and you don’t know, they’ll use it against you.” Sure enough, after doing his fancy footwork, he’d hear the dreaded question, “Do you break on the two?” At that time, these theoretical points about clave and dancing didn’t jive with Eddie. Fortunately for Eddie, he’d been on two all his life–he just didn’t know it. And June continued harping, “It’s going to enhance you as a dancer, as a teacher and as a choreographer. You’ll go a lot further with this knowledge.” But Eddie fought it. Fifteen years went by before he really learned.

Thanks to June Laberta, Eddie’s steps all have names.

This repertoire of steps and turns, with their corresponding names, provides a way of relating to students academically. Eddie’s class syllabus documenting three hundred steps strangely parallels the habits of the old scholars of dance at the ballrooms. His laboratory is self-contained–sometimes steps spring up spontaneously in the class. Sometimes, just fooling around with a little break or phrase, a step is born. Nowadays, part of the fun is to invent a step and then find a name for it.

Today, dancing students are surpassing people who have been dancing socially for many years. Mr. T. gets calls all the time, “I’m a great dancer, people stop to watch me.” One visit to a class and they get humbled. Natural talent is a plus, but Torres warns, “Amongst Latinos, we believe that we can walk on the dance floor and we just do it because we’re Latinos, we’re born with this. This is just not true.”

“I’ve danced out of joy, I’ve danced out of pain.

This is the kind of dance where if you want to jump up and say ‘Azucar!’ like Celia, and you want to move your shoulders and bob your head, this is where you can do it and it’s O.K. It’s cool. And it’s hip. You can be you.”

We must thank Tito Puente for showcasing salsa dancing in most of his concerts and for making his little speech about the importance of the dance when he presents our beloved Latin dancers.

Eddie’s accomplishments include his many collaborations with the Tito Puente Orchestra, choreographing music videos for artists like Ruben Blades, Orquesta de la Luz, Tito Nieves, José Alberto El Canario, David Byrne, founding a dance company, dancing for the President George Bush, performing.at Carnegie Hall, the Apollo Theater, Madison Square Garden.

Tratto da: www.eddietorres.com

I video di…

Eddie Torres

Video tratti da Youtube.com

I saluti di Eddie Torres a Lasalsavive.org

Eddie Torres balla il boogaloo – Eso se baila asi, Willie Colon

Eddie Torres & Nancy Ortiz – Arinanara

Eddie Torres & Nancy Ortiz

Eddie Torres & Tito Puente

Workshop di Pachanga di Eddie e Maria Torres durante il Simposalsa 2007 di Madrid.